TABI: Transcriptomic Analyses through Bayesian Inference

Supervised by: Dr. Stefano Mangiola & Prof. Tony Papenfuss

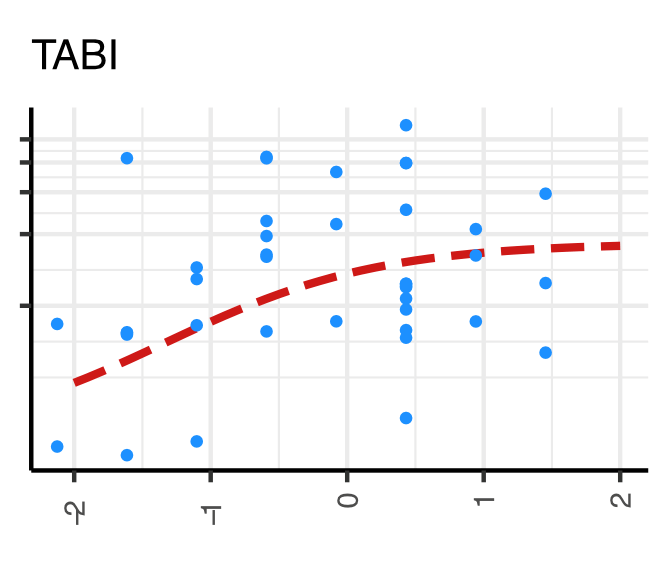

Example fit of TABI to mRNA expression data over a continous covariate

Example fit of TABI to mRNA expression data over a continous covariate

Changes in the dynamics of progressive disease often accompany changes in gene expression. Hence, detecting which genes are differentially expressed across disease stages, and when changes to gene expression occur, can provide insight into the nature and progression of the disease. Many popular software tools for determining which genes are differentially transcribed (e.g. edgeR, DESeq2, baySeq) already exist. However, these techniques lack standard procedures to estimate when, in terms of disease stage, changes occur. Typically, researchers interested in determining what disease stage gene expression changes occurred bin patient samples from multiple stages into groups; creating a conflict between their ability to detect ‘which’ and the specificity of their estimate of ‘when’.

My aim was to develop and apply a Bayesian differential expression inference model designed to help researchers more precisely identify ‘when’ gene expression changes occur. This model, TABI, works by fitting a sigmoidal (or ‘s’ shaped) curve to RNAseq count data measured against a continuous (e.g. survival rate) or pseudo-continuous (e.g. some cancer staging scales) variable. The initial outline of the sigmoidal model and corresponding R-package was developed during the PhD of my advisor (Dr. Stefano Mangiola). Thus, my precise role in this work was to modify the mathematical model and R-package Stan code for it to be more suited to testing using real datasets (e.g. I added overdispersion parameters to the model to account for non-biological sources of read count variation). Additionally, I compared the model to relevant popular software (edgeR, DESeq2, baySeq) using both simulated and real prostate cancer data (primary prostate cancer tumor samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas, 37318 transcripts, 135 individuals). Specifically, I assessed the performance of each software package in three main criteria: running time, computational resources, accurate identification of data features (true simulated parameters or recapitulation of prostate cancer biomarkers).

I found our TABI model was best able to recapitulate a pattern of gene expression changes consistent with current understandings of the disease (early inhibition of normal immunological processes, late dysregulation of cell adhesion and movement). However, using RStan to fit TABI’s model required a lot of computation resources (>4 CPUs, and >5 minutes for a single gene, with 10 samples). I performed considerable troubleshooting to try to resolve this issue (e.g. fixing one parameter at time and testing time taken). Ultimately, I ran out of time to resolve this issue, and the project was abandoned.