How to code up your own Wright-Fisher model in R to explore genetic drift

Tutorial with R code and interactive plots for readers to investigate how different evolutionary parameters impact population allele frequency across generations using the Wright-Fisher model

Imagine an isolated population. At one genetic locus, there are two variants in this population: the more common A allele (80%), and the less common allele.

If you were lucky enough to visit this population 100 years later, do you think you’d still find allele A in 20% of the chromosomes in this population?

If you said, it depends, you’d be correct.

The Wright-Fisher Model is a mathematical model that can help us understand some of the specific circumstances that cause allele frequency in a population to change over time - and thus, develop a nuanced answer to this question. In this article I’m going to use this model to explore how population size, and allele frequency impact the process of genetic drift through simulation.

Table of contents

- Genetic Drift Overview

- Introduction to the Wright-Fisher Model

- Writing R codel

- Plotting population allele frequency simulations

- Varying both initial allele frequency and population size - our final question answer

Genetic Drift Overview

Genetic variation may not be passed down from one generation to another for a number of unpredictable reasons.

For example, an individual dies before reproducing because they’re one of the unlucky few to have a fridge fall on them from a great height.

Or like flipping a coin and getting heads each time, a father could have many daughters and no sons, and therefore none of his offspring inherit any genetic variation on his Y chromosome.

This randomness in individual survival, reproduction, and inheritance can change the frequency of alleles in a population over time - a process called genetic drift.

While it’s tough to make any predictions about these random processes at the individual level, we can make some inferences about the likely direction and significance of genetic drift at a population level.

Setting up the Wright-Fisher Model

Independently derived by Sewall Wright and Ronald A. Fisher in the early 20th century, the Wright-Fisher model is a mathematical description of the change in population allele frequency at a single locus under specific simplifying conditions: no selection, no mutation, no overlap between generations, random mating, finite and fixed population size.

While these conditions are entirely unrealistic for real-world populations, the resulting Wright-Fisher model is still very useful for testing hypotheses on real data. Additionally, as we will use it today, the Wright-Fisher model is a great tool to explore to develop intuition about genetic drift, and how this process is impacted by two important factors: population size and allele frequency.

In this article, under this model allele frequency at each generation (

Variance and expected allele frequencies under the Wright-Fisher model

If you’ve had some statistical training, you may be able to work out the expected value and variance of

If you can’t work this out alone, check out the <a href=“https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binomial_distribution>binomial distribution wikipedia page to try to figure these values out for yourself before checking the answers below.

Under this Wright-Fisher model notation, what is the expected frequency of the ‘

In mathematical notation:

In words: The frequency of the

What is the variance in the frequency of the ‘

In mathematical notation:

In words: The frequency of the

In a practical non-mathematical sense what features what am I referring to, when I am asking for the expected frequency and variance in the frequency of the p allele at generation

If we could repeatably go back an infinite number of times to the generation t-1 and then observe the allele frequency at generation t, what allele frequency would we expect to see across these repetitions at the t generation on average? How much variation across would we see across these repetitions?

You could think about these repetitions as infinite ‘multiple parallel universes’ which were set up to be exactly the same at generation t, and then left to progress without inference.

Trying to answer our original question with Wright-Fisher model formulas alone

Going back to our original scenario and question: If you visited the same population 100 years later, do you think you’d still find allele A in 20% of the chromosomes in this population?

If you assumed this population met all the conditions for the Wright-Fisher model, and considered the above formula for the expected allele frequency, you might say yes. The expected value of the allele frequency for one generation is just the allele frequency for the previous generation.

But this answer is only correct for an infinitely large population. Or a population with only one allele (i.e. everyone is homozygous for the A allele).

In all other situations, the frequency of selectively neutral variants will randomly fluctuate from generation to generation because of the inherent randomness in the processes which lead to gametes ultimately becoming offspring. And of course, because we’re assuming no mutation, as soon as the A allele isn’t transmitted on to the next generation … that’s it - there’s no more A allele in this population forever.

Using Wright-Fisher model simulations to answer our question

The probability that the A allele isn’t passed on to the next generation depends on how many copies and individuals in the population currently carry copies of the A allele. Clearly, the more common the A allele is (i.e. higher A allele frequency), the more likely it is to be passed on. Hence,Population size is also important: if our original population consisted of 5 individuals, then only ~2* people would carry at least one copy of the A allele; if instead the population consisted of a million individuals, then ~360,000* people would carry at least one copy. The likelihood that 2, compared to 360,000 individuals, don’t pass on any of their A alleles is much higher.

… But how much impact does this population size difference truly have on the chance that the A allele becomes fixed?

… And more generally, how does the combination of population size and allele frequency impact the likelihood that an allele becomes fixed (in other words, the only allele in the population)? How do these factors impact how dramatic the change can be in allele frequency is from one generation to another?

… And, when should we be concerned that a population is too small to ensure genetic diversity is maintained (i.e. neither the A or a allele becomes fixed)?

It’s time to stop thinking about how allele frequency might change over an infinite number of parallel universes, and instead start simulating allele frequency across generations using the Wright-Fisher Model.

*How did I come up with these values for the number of individuals in this population who carry at least one copy of the A allele ?

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium!

If you look at the assumptions underlying the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium formula, you’ll notice that they are eerily similar to those of the Wright-Fisher Model stated above. The main difference between the two models is the situation each of these formulas is built to explore; Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium is about relating genotype to allele frequency in the same generation, the Wright-Fisher model is about relating the allele frequency from one generation to another.

Under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, the proportion of individuals carrying at least one copy of an allele, p, is:

In our scenario, the frequency of the A allele is 20% (i.e.

$ = 2 0.8 + 0.2 ^{2} $

$ = 0.36 $

Thus, for a population of 5 individuals, we expect $ 5 = 1.8 $ (i.e. ~2) people to carry at least one copy of the A allele. Comparatively for a population of a million individuals, we expect $ 10^6 = 360,000 $ people to carry at least one copy of the A allele.

Writing R code to simulate population allele frequency change over time using the Wright-Fisher model

Now, to explore allele frequency over time using the Wright-Fisher model let’s first set up R code to simulate allele frequency in a subsequent generation.

In standard conceptions of the binomial model, we often refer to ‘success’, and ‘trials’. For instance if we’re interested in the number of heads observed after flipping a coin 10 times, we define success is ‘observing heads in a single coin flip’, and the trials are ‘each coin flip’ (so the number of trials is 10).

The R code to simulate one run of 10 coin flips (aforementioned scenario) is:

# the total number of trials

n_coin_flips <- 10

# chance of observing success (heads) at a single trial:

heads_chance <- 0.5

# now let's see how many heads we observe in one 'run' of 10 coin flips

rbinom(n = 1, #number of simulations to make

prob = heads_chance, # probability of success at each trial

size = n_coin_flips) # number of trials ## [1] 4Note: take care - the mathematical notation often used to denote the number of trials (size): in R code,

First step: using rbinom to simulate allele frequency in the next generation

In the Wright-Fisher model, we can consider thesuccessevent in the binomial variable context to be ‘a single gamete with an A allele is involved in sexual reproduction, and ultimately becomes an offspring’, and thenumber of trials to refer to ‘the total number of gametes which ultimately make up the next generation’(i.e. twice the population size).

Unlike the coin flip scenario, we are not interested in the number of successes. Instead, in this case we care about the proportion of successes (the allele frequency in the next generation). We can easily calculate the proportion of success as the number of successes divided by 2 times population size (the total number of gametes), as one of our assumptions is that our population size remains fixed.

Can you use the above two paragraphs to adapt the coin flip code to simulate allele frequency in the subsequent generation?

Let population size (pop_size) be allele_freq) be

Let’s see an example of adapting the coin flip code

pop_size = 5

allele_freq = 0.2

# total number of 'A' alleles in the next generation

al_total = rbinom(n = 1,

size = 2*pop_size,

prob = allele_freq

)

# frequency of 'A' alleles in the next generation

al_total / 2 * pop_size## [1] 2.5Second step: Writing a more readable function to simulate allele frequency in the next generation

Now that we have the basic code to simulate allele frequency change from one generation to the next, let’s turn this code into a more readable function, wf_sim. This function will take two parameters (allele_freq, pop_size) as inputs and then uses the Wright-Fisher model to simulate allele frequency in the subsequent generation.

# Function - use the Wright-Fisher Model to simulate

# what the allele frequency in the next generation could be

# from the allele frequency in the current generation and population size

wf_sim <- function(allele_freq, pop_size) {

# let this be allele frequency for any given allele, e.g. A

# the below calculates total number of copies of this allele in the next generation

al_total<- rbinom(n = 1,

size = 2*pop_size,

prob = allele_freq

)

# convert this number to allele frequency

return(al_total / (2*pop_size))

}Can you use the above wf_sim function to simulate allele frequency in the subsequent generation? Let population size (pop_size) be allele_freq) be

Reveal example code

wf_sim(allele_freq = 0.2,

pop_size = 5

)## [1] 0.1Third step: Write a function to simulate allele frequency changes across an arbitrary number of generations

And now, let’s create an R function called wf_sim_n_gen that applies the above wf_sim function repeatedly - so we can simulate allele frequency in as many generations (n_gen) in the future as we like.

# Expand the above code to simulate allele frequency

# using the Wright-Fisher model

# over an arbitrary number of generations (n_gen)

wf_sim_n_gen <- function(init_allele_freq,

pop_size,

n_gen) {

# set up initial allele freq vector

allele_freq = rep(NA, n_gen+1)

allele_freq[1] = init_allele_freq

# then iterative apply the Wright-Fisher model

# to get the allele frequency at the next generation

# until this has been done for the requested number of generations

for(generation in 2:c(n_gen+1)){

allele_freq[generation] = wf_sim(allele_freq[generation - 1],

pop_size)

}

allele_freq_df = data.frame("allele_freq" = allele_freq,

"generation" = 0:c(n_gen))

return(allele_freq_df)

}Now test out the wf_sim_n_gen function yourself.

How would you use the above wf_sim_n_gen function to simulate allele frequency in the next generation of this population (initial allele frequency of 20%, population size of 5)?

Reveal example code.

wf_sim_n_gen(init_allele_freq = 0.5,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 1)## allele_freq generation

## 1 0.5 0

## 2 0.6 1

How would you use the above wf_sim_n_gen function to simulate allele frequency in the next 10 generations of a population (initial allele frequency of 20%, population size of 5)?

wf_sim_n_gen(init_allele_freq = 0.5,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 10)## allele_freq generation

## 1 0.5 0

## 2 0.7 1

## 3 0.8 2

## 4 0.8 3

## 5 0.8 4

## 6 0.8 5

## 7 0.5 6

## 8 0.8 7

## 9 0.8 8

## 10 0.9 9

## 11 0.8 10

Plotting population allele frequency changes over multiple generations

It’s hard to interpret what our simulated allele frequency changes over generations tell us about how population size impacts genetic drift from these tables alone; it will be much easier to understand what is going on by plotting this data.

Plotting the simulated data will be especially helpful when we try to perform simulations over a wide variety of population sizes, and allele frequencies; and also, when we try to observe a variety of possible allele frequency trajectories by repeated simulation.

Let’s start by plotting our results from the previous question (i.e., tracking allele frequency across 10 generations in a single population of 5 individuals where allele A initially has a frequency of 20%).

suppressWarnings(suppressMessages(library(dplyr)))

suppressMessages(library(ggplot2))

suppressMessages(library(plotly))

suppressMessages(library(RColorBrewer))

plot = wf_sim_n_gen(init_allele_freq = 0.5,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 10) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=generation,

y=allele_freq)

) +

geom_line() +

theme_bw() +

labs(x = "Generation",

y = "Frequency of the'A' Allele") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 5)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 10),

limits = c(0,1))

ggplotly(plot)

Parse your cursor over the line plotted above; you should be able to see the simulated values for each generation.

Expanding our Wright-Fisher model R function to perform varying and repeated simulations

Now, let’s create a function that allows us to go (and plot) further than our wf_sim_n_gen function: meaning we can now easily plot simulations with varied population sizes, varied initial allele frequency, in a repetitive manner (i.e. see multiple possible pathways for allele frequency to vary over time for the same population size and initial allele frequency).

To do this, I define a function rep_wf_n_gen using the R package purrr to iterate across all parameters I will need to: number of repetitions (n_reps), initial allele frequency (init_allele_freq), population size (pop_size), number of generations (n_gen).

library(purrr)

rep_wf_n_gen = function(n_reps,

init_allele_freq,

pop_size,

n_gen

){

all_sims = expand.grid(init_allele_freq = init_allele_freq,

pop_size = pop_size,

sim_idx = 1:n_reps,

n_gen = n_gen

)

wf_sim_all = purrr::pmap(all_sims,

function(init_allele_freq,

pop_size,

n_gen,

sim_idx){

return(

wf_sim_n_gen(init_allele_freq,

pop_size,

n_gen) %>%

mutate(init_allele_freq = init_allele_freq,

pop_size = pop_size,

sim_idx = sim_idx

)

)

}

)

wf_sim_all = purrr::list_rbind(wf_sim_all)

wf_sim_all = wf_sim_all %>%

mutate(sim_idx = as.factor(sim_idx))

return(wf_sim_all)

}Now try the rep_wf_n_gen function for yourself.

Can you perform one simulation of 10 generations of allele frequency changes using this function? As in earlier examples, let population size (pop_size) be allele_freq) be

Reveal code to answer the above question.

rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 1, #number of simulations - or repetitions

init_allele_freq = 0.2,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 10)## allele_freq generation init_allele_freq pop_size sim_idx

## 1 0.2 0 0.2 5 1

## 2 0.1 1 0.2 5 1

## 3 0.1 2 0.2 5 1

## 4 0.0 3 0.2 5 1

## 5 0.0 4 0.2 5 1

## 6 0.0 5 0.2 5 1

## 7 0.0 6 0.2 5 1

## 8 0.0 7 0.2 5 1

## 9 0.0 8 0.2 5 1

## 10 0.0 9 0.2 5 1

## 11 0.0 10 0.2 5 1Can you perform 10 simulations of 10 generations of allele frequency changes using the rep_wf_n_gen function? Once again, let population size (pop_size) be allele_freq) be

Reveal code to perform repeated simulated of the same population

data = rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 10,

init_allele_freq = 0.2,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 10)

# show only a random 10 rows as an example

dplyr::slice_sample(data, n = 10)## allele_freq generation init_allele_freq pop_size sim_idx

## 1 0.0 4 0.2 5 6

## 2 0.0 4 0.2 5 10

## 3 0.0 3 0.2 5 7

## 4 0.0 9 0.2 5 5

## 5 0.2 0 0.2 5 3

## 6 0.1 10 0.2 5 1

## 7 0.0 8 0.2 5 10

## 8 0.3 5 0.2 5 8

## 9 0.1 9 0.2 5 1

## 10 0.4 4 0.2 5 1

Plot multiple simulations of the same starting population

Now, let’s expand our previous plot where only considered one possible trajectory of allele frequency changes over generations to now consider 8 possible trajectories (i.e, like the code output for 10 different simulations written for the previous question - just now out replications).

plot = rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 8,

init_allele_freq = 0.2,

pop_size = 5,

n_gen = 10) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=generation, # on the x-axis, let's plot the generation number

y=allele_freq, # on the y-axis, let's plot the allele frequency at this gen

group = sim_idx,

color = sim_idx)) + # make a line per simulated population

geom_line() +

theme_bw() +

labs(x = "Generation",

y = "Frequency of the 'A' Allele") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 5)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 10),

limits = c(0,1)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Dark2", name = "Replication #")

ggplotly(plot)

Plot allele frequency changes over generations across differing population sizes

Now, let’s try to use the rep_wf_n_gen function to plot how population size differences impact the genetic drift process.

Can you use the rep_wf_n_gen function to perform 8 simulations across 50 generations for populations with initial A allele frequency of 20%? Use this function to simulate across several different population sizes (5, 10, 100, 10,000, 1,000,000).

Reveal code example.

data = rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 8,

pop_size = c(5,10^2,10^4, 10^6),

init_allele_freq = 0.2,

n_gen = 50

)

# show only a random 10 rows as an example

dplyr::slice_sample(data, n = 10)## allele_freq generation init_allele_freq pop_size sim_idx

## 1 0.1955500 23 0.2 1e+04 3

## 2 0.2050000 36 0.2 1e+02 3

## 3 0.1968815 50 0.2 1e+06 2

## 4 0.2017965 28 0.2 1e+06 5

## 5 0.0450000 40 0.2 1e+02 6

## 6 0.1000000 14 0.2 5e+00 3

## 7 0.2186000 38 0.2 1e+04 3

## 8 0.1350000 23 0.2 1e+02 7

## 9 0.2040000 12 0.2 1e+04 4

## 10 0.2023500 39 0.2 1e+04 2Now let’s plot this simulated data to improve our sense of how population size impacts the process of genetic drift:

plot = rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 8,

pop_size = c(5,10^2,10^4, 10^6),

init_allele_freq = 0.2,

n_gen = 50) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=generation,

y=allele_freq,

group = sim_idx,

color = sim_idx)

) +

geom_line() +

theme_bw() +

facet_wrap(vars(pop_size),

labeller = labeller(pop_size =

~paste0("Pop. size = ", .x)

),

axes = "all") +

labs(x = "Generation",

y = "Frequency of 'A' Allele") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 5)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 10),

limits = c(0,1)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Dark2",

name = "Replication #") +

theme(legend.position = "none")

ggplotly(plot)

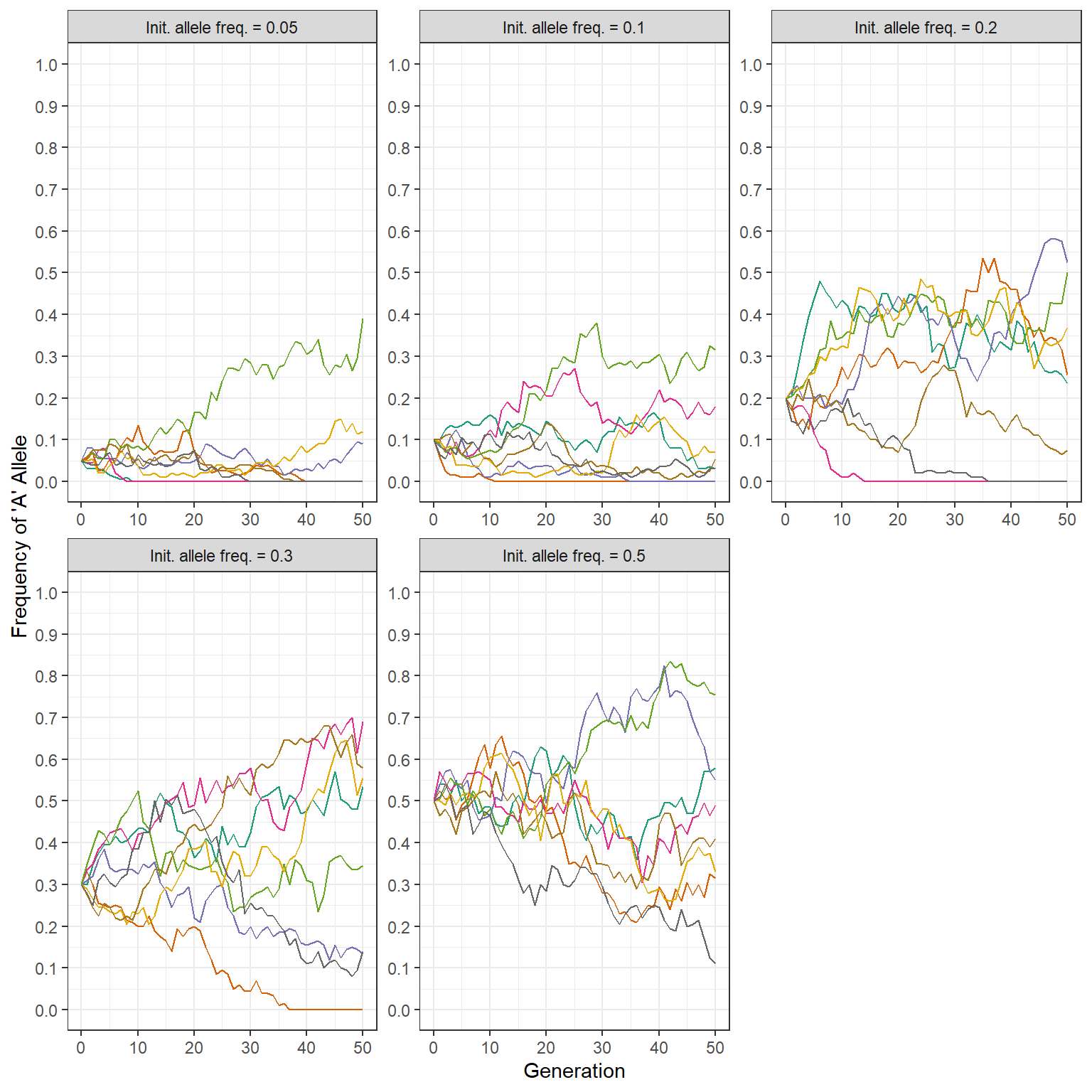

Plot allele frequency over generations across different initial allele frequencies

Next, can you use the rep_wf_n_gen function to perform 8 simulations across 50 generations, for populations consisting of 100 individuals? For this question, vary the initial allele frequency (0.05,0.1,0.2,0.3,0.5).

Reveal example code answer

data = rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 8,

init_allele_freq = c(0.05,0.1,0.2,0.3,0.5),

pop_size = 100,

n_gen = 50

)

# show only a random 10 rows as an example

dplyr::slice_sample(data, n = 10)## allele_freq generation init_allele_freq pop_size sim_idx

## 1 0.105 33 0.05 100 5

## 2 0.520 21 0.50 100 3

## 3 0.235 20 0.20 100 4

## 4 0.045 20 0.10 100 1

## 5 0.370 24 0.50 100 4

## 6 0.330 4 0.30 100 8

## 7 0.745 36 0.30 100 3

## 8 0.035 26 0.05 100 1

## 9 0.110 38 0.30 100 1

## 10 0.675 38 0.50 100 3Ok, great - and now let’s plot this resulting simulated data to demonstrate how different allele frequencies impact the genetic drift process.

rep_wf_n_gen(n_reps = 8,

init_allele_freq = c(0.05,0.1,0.2,0.3,0.5),

pop_size = 100,

n_gen = 50

) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=generation,

y=allele_freq,

group = sim_idx,

color = sim_idx)

) +

geom_line() +

theme_bw() +

facet_wrap(vars(init_allele_freq),

labeller = labeller(init_allele_freq =

~paste0("Init. allele freq. = ", .x)

),

axes = "all"

) +

labs(x = "Generation",

y = "Frequency of 'A' Allele") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 5)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 10),

limits = c(0,1)) +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Dark2", name = "Replication #") +

theme(legend.position = "none")

Putting it all together: varying both initial allele frequency and population size

We’ve seen how to use the Wright-Fisher model to explore how allele frequency and population size impact the process of genetic drift when considered individually… But we haven’t tried to vary them together.

I leave this last piece of the puzzle as an exercise for you, dear reader. On this page you have all the code you might need to explore this final aspect and develop a complete answer to the overarching question of this article:

If you were lucky enough to visit this population 100 years later, do you think you’d still find allele A in 20% of the chromosomes in this population?

*P.S. I will be fleshing out this article with more explanations over time, but this might be a slow process. Please reach out if you’ve found part of this article helpful, but there is a particular section where you’d like more information / detail.