Predicting the cross population portability of human eQTLs

Master of Science Thesis Project supervised by: Dr. Irene Gallego Romero & Dr. Christina Azodi

Motivation

Personalised medicine, the targeting of treatment decisions to a patient’s genetic makeup, is the future of medical practice. Using this approach, doctors can select the best medicine for their patients without the trial and error that causes dangerous delays to treatment today.

The most glaring obstacle to the more widespread use of personalised medicine is our research subjects: genetics research participants are typically individuals of European ancestry (see 1,2,3). At first, this may seem like a minor problem since the same biological pathways connect genes with disease for every human being. However, we find different associations between genetics and disease when we repeat studies across ancestries or socio-economic statuses (e.g. 4,5,6,7). Thus, the mathematical models we use to predict the individual genetic risk of developing disease are often much less accurate for anyone who falls outside of the narrowly defined ‘European’ ancestry: a phenomenon known as the ‘non-portability’ problem. If we rolled out personalised medicine today, the ‘non-portability’ problem would lead us to further entrench current health inequalities.

Aims and methods

One way to improve the equitability of these precision medicine models is to better understand which genetic associations are likely to differ across human groups and why they differ. Towards this overarching goal, I developed machine learning models that predict whether or not one type of genetic association (expression quantitative trait loci, eQTL) is likely to be different across human groups.

(A): Integrate summary statistics from published eQTL studies.

(B): Classify gene-SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphisms) pairs as being eQTLs or not, and then, eQTLs as being portable across populations, or not.

(C): Use publicly available datasets to obtain, and engineer the genomic features of eQTLs.

(D): Use ~10% of these eQTLs to train machine learning models.

(E): Test models performance, use the best model to investigate features which differentiate portable and non-portable eQTLs.

I first tested a variety of approaches to developing these models to uncover what approach would produce the highest-performing models. Then, I used this preferred approach to create models and investigate what information they used to successfully identify which genetic associations are different across human populations.

Conclusions

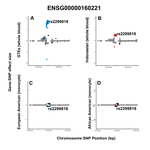

I demonstrated that applying a multi-adaptive shrinkage method (mashr) to these summary statistics improved power, and increased eQTL and eGene sharing across populations. I found that of all machine learning algorithms tested, decision-tree based classifiers (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) were best able to recapitulate portable and non-portable eQTLs classes on an independent held-out test set. Then, after uncovering the optimal machine learning training set up, I trained a model for every possible pairwise population portability comparison (median improvement over random chance auPRC= 0.073 across eight models in two cell types). Applying Leave-One-Feature-Out feature importance procedures to these models found no feature category, or set of features, had a significant or consistent greatest impact on model performance. Finally, by comparing my datasets with the set of 6 GTEx identified population-biased whole-blood eQTLs, I uncovered a plausible example of an eQTL portable in a tissue-dependent manner (rs2299818_ENSG00000160221).